AGXStarseed

Well-Known Member

(Not written by me. This article is from November 2017 and I thought what it talked about was interesting, so I'm posting it here to see what your opinions are on this topic)

The Pros and Cons of Reintroducing Long-Extinct Mammals, Birds and Amphibians

There's a new buzzword that has been making the rounds of trendy tech conferences and environmental think tanks: de-extinction. Thanks to ongoing advances in DNA recovery, replication and manipulation technology, as well as the ability of scientists to recover soft tissue from fossilized animals, it may soon be possible to breed Tasmanian Tigers, Woolly Mammoths and Dodo Birds back into existence, presumably undoing the wrongs that mankind inflicted on these gentle beasts in the first place, hundreds or thousands of years ago.

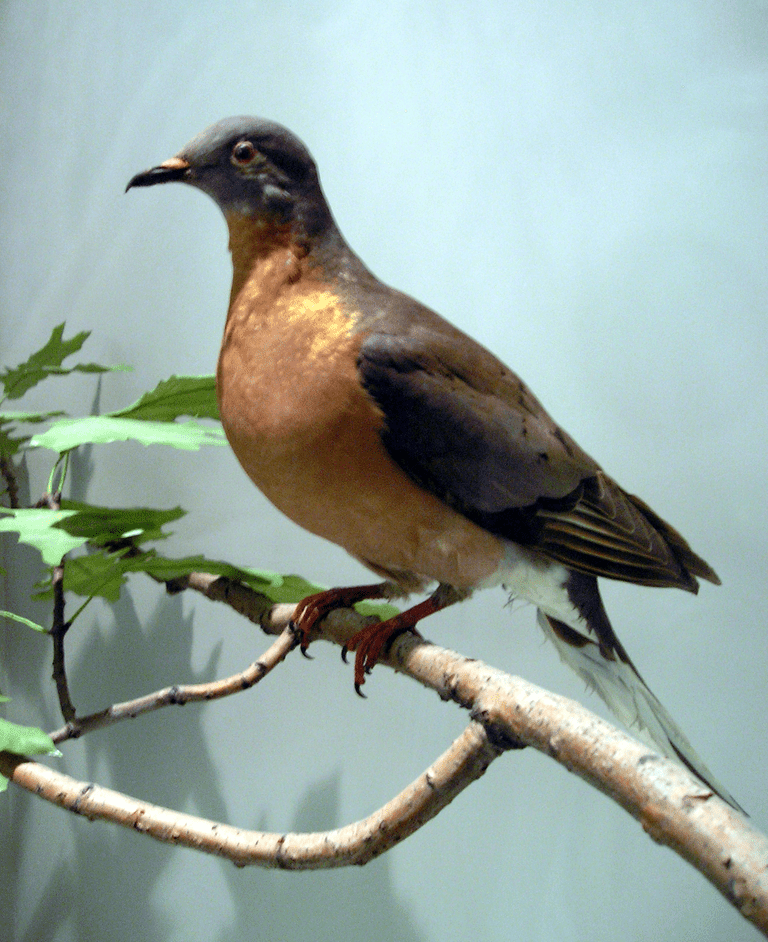

The Passenger Pigeon, a possible candidate for de-extinction (Wikimedia Commons).

The Technology of De-Extinction

Before we get into the arguments for and against de-extinction, it's helpful to look at the current state of this rapidly developing science. The crucial ingredient of de-extinction, of course, is DNA, the tightly wound molecule that provides the genetic "blueprint" of any given species. In order to de-extinct, say, a Dire Wolf, scientists would have to recover a sizable chunk of this animal's DNA, which is not so far-fetched considering that Canis dirus only went extinct about 10,000 years ago and various fossil specimens recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits have yielded soft tissue.

Wouldn't we need all of an animal's DNA in order to bring it back from extinction? No, and that's the beauty of the de-extinction concept: the Dire Wolf shared enough of its DNA with modern canines that only certain specific genes would be required, not the entire Canis dirus genome.

The next challenge, of course, would be to find a suitable host to incubate a genetically engineered Dire Wolf fetus; presumably, a carefully prepared Great Dane or Grey Wolf female would fit the bill. (This is the technique popularly referred to as "cloning," though it would involve the reconstruction, rather than the duplication, of a given genome.)

There is another, less messy way to "de-extinct" a species, and that's by reversing thousands of years of domestication. In other words, scientists can selectively breed herds of cattle to encourage, rather than suppress, "primitive" traits (such as an ornery rather than a peaceful disposition), the result being a close approximation of an Ice Age Auroch. This technique could conceivably even be used to "de-breed" canines into their feral, uncooperative Grey Wolf ancestors, which may not do much for science but would certainly make dog shows more interesting.

This, by the way, is the reason virtually no one seriously talks about de-extincting animals that have been extinct for millions of years, like dinosaurs or marine reptiles. It's difficult enough to recover viable fragments of DNA from animals that have been extinct for thousands of years; after millions of years, any genetic information will be rendered completely irrecoverable by the fossilization process. Jurassic Park aside, don't expect anyone to clone a Tyrannosaurus Rex in your or your children's lifetime!

Arguments in Favor of De-Extinction

Just because we may, in the near future, be able to de-extinct vanished species, does that mean we should?

Some scientists and philosophers are very bullish on the prospect, citing the following arguments in its favor:

We can undo humanity's past mistakes. In the 19th century, Americans who didn't know any better slaughtered Passenger Pigeons by the millions; generations before, the Tasmanian Tiger was driven to near-extinction by European immigrants to Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania. Resurrecting these animals, this argument goes, would help reverse a huge historical injustice.

We can learn more about evolution and biology. Any program as ambitious as de-extinction is certain to produce important science, the same way the Apollo moon missions helped usher in the age of the personal computer. We may potentially learn enough about genome manipulation to cure cancer or extend the average human's life span into the triple digits.

We can counter the effects of environmental depredation. An animal species isn't important only for its own sake; it contributes to a vast web of ecological interrelationships, and makes the entire ecosystem more robust. Resurrecting extinct animals may be just the "therapy" our planet needs in this age of global warming and human overpopulation.

Arguments Against De-Extinction

Any new scientific initiative is bound to provoke a critical outcry, which is often a knee-jerk reaction against what critics consider "fantasy" or "bunk." In the case of de-extinction, though, the naysayers may have a point, as they maintain that:

De-extinction is a PR gimmick that detracts from real environmental issues. What is the point of resurrecting the Gastric-Brooding Frog (to take just one example) when hundreds of amphibian species are on the brink of succumbing to the chytrid fungus? A successful de-extinction may give people the false, and dangerous, impression that scientists have "solved" all of our environmental problems.

A de-extincted creature can only thrive in a suitable habitat. It's one thing to gestate a Saber-Toothed Tiger fetus in a Bengal tiger's womb; it's quite another to reproduce the ecological conditions that existed 100,000 years ago, when these predators ruled Pleistocene North America. What will these tigers eat, and what will be their impact on existing mammal populations?

There's usually a good reason why an animal went extinct in the first place. Evolution can be cruel, but it's never wrong.

Human beings hunted Woolly Mammoths to extinction over 10,000 years ago; what's to keep us from repeating history? (If you say "the rule of law," bear in mind that seriously endangered mammals are illegally hunted every day, especially in Africa.)

De-Extinction: Do We Have a Choice?

In the end, any genuine effort to de-extinct a vanished species will probably have to win the approval of various government and regulatory agencies, a process that might take years, especially in our current political climate. Once introduced into the wild, it can be difficult to keep an animal from spreading into unexpected niches and territories--and, as mentioned above, not even the most far-sighted scientist can gauge the environmental impact of a resurrected species. (What if that herd of Aurochs develops a taste for grain, rather than grass? What if a burgeoning population of Woolly Mammoths manages to drive the African elephant to extinction?) One can only hope that, if de-extinction goes forward, it will be with a maximal amount of care and planning--and a healthy regard for the law of unintended consequences.

Source: How Scientists Are Playing Frankenstein with Extinct Animals

Related: How to Resurrect an Extinct Animal in 10 (Not So Easy) Steps

Can We Bring the Dodo Bird Back to Life?

The Pros and Cons of Reintroducing Long-Extinct Mammals, Birds and Amphibians

There's a new buzzword that has been making the rounds of trendy tech conferences and environmental think tanks: de-extinction. Thanks to ongoing advances in DNA recovery, replication and manipulation technology, as well as the ability of scientists to recover soft tissue from fossilized animals, it may soon be possible to breed Tasmanian Tigers, Woolly Mammoths and Dodo Birds back into existence, presumably undoing the wrongs that mankind inflicted on these gentle beasts in the first place, hundreds or thousands of years ago.

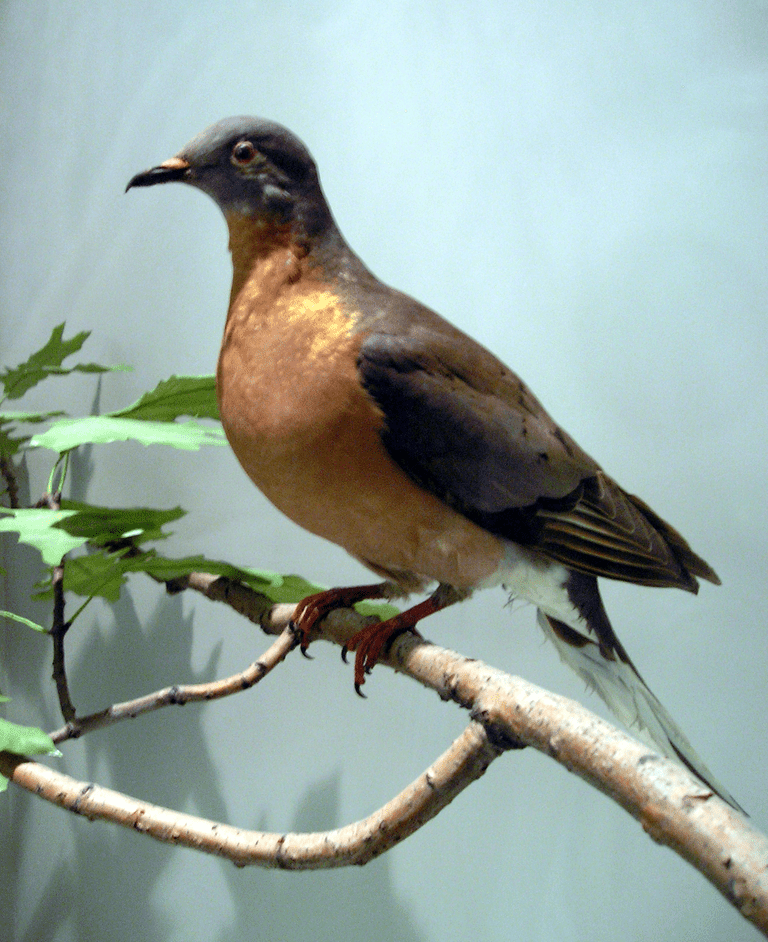

The Passenger Pigeon, a possible candidate for de-extinction (Wikimedia Commons).

The Technology of De-Extinction

Before we get into the arguments for and against de-extinction, it's helpful to look at the current state of this rapidly developing science. The crucial ingredient of de-extinction, of course, is DNA, the tightly wound molecule that provides the genetic "blueprint" of any given species. In order to de-extinct, say, a Dire Wolf, scientists would have to recover a sizable chunk of this animal's DNA, which is not so far-fetched considering that Canis dirus only went extinct about 10,000 years ago and various fossil specimens recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits have yielded soft tissue.

Wouldn't we need all of an animal's DNA in order to bring it back from extinction? No, and that's the beauty of the de-extinction concept: the Dire Wolf shared enough of its DNA with modern canines that only certain specific genes would be required, not the entire Canis dirus genome.

The next challenge, of course, would be to find a suitable host to incubate a genetically engineered Dire Wolf fetus; presumably, a carefully prepared Great Dane or Grey Wolf female would fit the bill. (This is the technique popularly referred to as "cloning," though it would involve the reconstruction, rather than the duplication, of a given genome.)

There is another, less messy way to "de-extinct" a species, and that's by reversing thousands of years of domestication. In other words, scientists can selectively breed herds of cattle to encourage, rather than suppress, "primitive" traits (such as an ornery rather than a peaceful disposition), the result being a close approximation of an Ice Age Auroch. This technique could conceivably even be used to "de-breed" canines into their feral, uncooperative Grey Wolf ancestors, which may not do much for science but would certainly make dog shows more interesting.

This, by the way, is the reason virtually no one seriously talks about de-extincting animals that have been extinct for millions of years, like dinosaurs or marine reptiles. It's difficult enough to recover viable fragments of DNA from animals that have been extinct for thousands of years; after millions of years, any genetic information will be rendered completely irrecoverable by the fossilization process. Jurassic Park aside, don't expect anyone to clone a Tyrannosaurus Rex in your or your children's lifetime!

Arguments in Favor of De-Extinction

Just because we may, in the near future, be able to de-extinct vanished species, does that mean we should?

Some scientists and philosophers are very bullish on the prospect, citing the following arguments in its favor:

We can undo humanity's past mistakes. In the 19th century, Americans who didn't know any better slaughtered Passenger Pigeons by the millions; generations before, the Tasmanian Tiger was driven to near-extinction by European immigrants to Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania. Resurrecting these animals, this argument goes, would help reverse a huge historical injustice.

We can learn more about evolution and biology. Any program as ambitious as de-extinction is certain to produce important science, the same way the Apollo moon missions helped usher in the age of the personal computer. We may potentially learn enough about genome manipulation to cure cancer or extend the average human's life span into the triple digits.

We can counter the effects of environmental depredation. An animal species isn't important only for its own sake; it contributes to a vast web of ecological interrelationships, and makes the entire ecosystem more robust. Resurrecting extinct animals may be just the "therapy" our planet needs in this age of global warming and human overpopulation.

Arguments Against De-Extinction

Any new scientific initiative is bound to provoke a critical outcry, which is often a knee-jerk reaction against what critics consider "fantasy" or "bunk." In the case of de-extinction, though, the naysayers may have a point, as they maintain that:

De-extinction is a PR gimmick that detracts from real environmental issues. What is the point of resurrecting the Gastric-Brooding Frog (to take just one example) when hundreds of amphibian species are on the brink of succumbing to the chytrid fungus? A successful de-extinction may give people the false, and dangerous, impression that scientists have "solved" all of our environmental problems.

A de-extincted creature can only thrive in a suitable habitat. It's one thing to gestate a Saber-Toothed Tiger fetus in a Bengal tiger's womb; it's quite another to reproduce the ecological conditions that existed 100,000 years ago, when these predators ruled Pleistocene North America. What will these tigers eat, and what will be their impact on existing mammal populations?

There's usually a good reason why an animal went extinct in the first place. Evolution can be cruel, but it's never wrong.

Human beings hunted Woolly Mammoths to extinction over 10,000 years ago; what's to keep us from repeating history? (If you say "the rule of law," bear in mind that seriously endangered mammals are illegally hunted every day, especially in Africa.)

De-Extinction: Do We Have a Choice?

In the end, any genuine effort to de-extinct a vanished species will probably have to win the approval of various government and regulatory agencies, a process that might take years, especially in our current political climate. Once introduced into the wild, it can be difficult to keep an animal from spreading into unexpected niches and territories--and, as mentioned above, not even the most far-sighted scientist can gauge the environmental impact of a resurrected species. (What if that herd of Aurochs develops a taste for grain, rather than grass? What if a burgeoning population of Woolly Mammoths manages to drive the African elephant to extinction?) One can only hope that, if de-extinction goes forward, it will be with a maximal amount of care and planning--and a healthy regard for the law of unintended consequences.

Source: How Scientists Are Playing Frankenstein with Extinct Animals

Related: How to Resurrect an Extinct Animal in 10 (Not So Easy) Steps

Can We Bring the Dodo Bird Back to Life?